Celebrating Seven Years of Hicatee Awareness Month

“Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we are waiting for. We are the change we seek.” Barack Obama

Hicatee Awareness Month was born out of a need – as are many things. The Hicatee turtle was on the brink of extinction. Belize was identified as the stronghold for the species throughout its small range. Yet, how do you get an entire country to care about saving one species of turtle? And even more challenging – a turtle that is entirely aquatic and seldom seen, so is most recognized as a delightful and celebratory meal?

With baby steps as well as trial and error.

In 2015, I designed a t-shirt with the Mountain Printing Company in the states. The shirt displayed a photo of the first Hicatee hatchling to the HCRC (Freckles) with #SaveTheHicatee written underneath. The turtle was perfectly adorable and a hit with kids. I was excited that this was the first significant material I had created for the purpose of conservation.

Soon after the shirts were delivered to Belize, Jacob Marlin wore his on the Hokey Pokey to travel from Mango Creek to Placencia. He ran into an old friend from the village, who said to him, “Your shirt is making me hungry!”

Jacob later told me the story and it stuck with me. Not as a failure but as a lesson and an opportunity. We had to do more and we had to think differently.

Richard and Carol Foster were finishing a documentary film that described the plight of the Hicatee in Belize. BFREE and Turtle Survival Alliance needed to share it with audiences in Belize who could care about the species and do something about it.

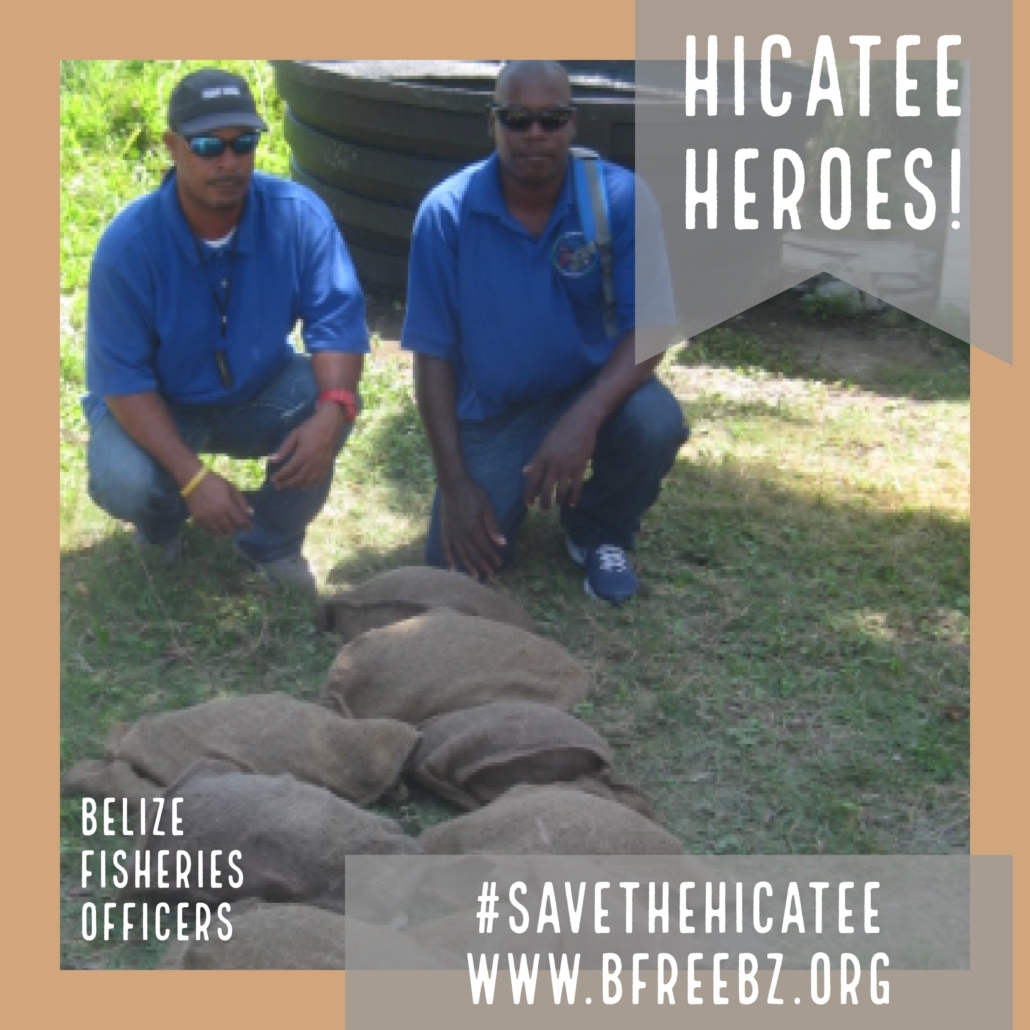

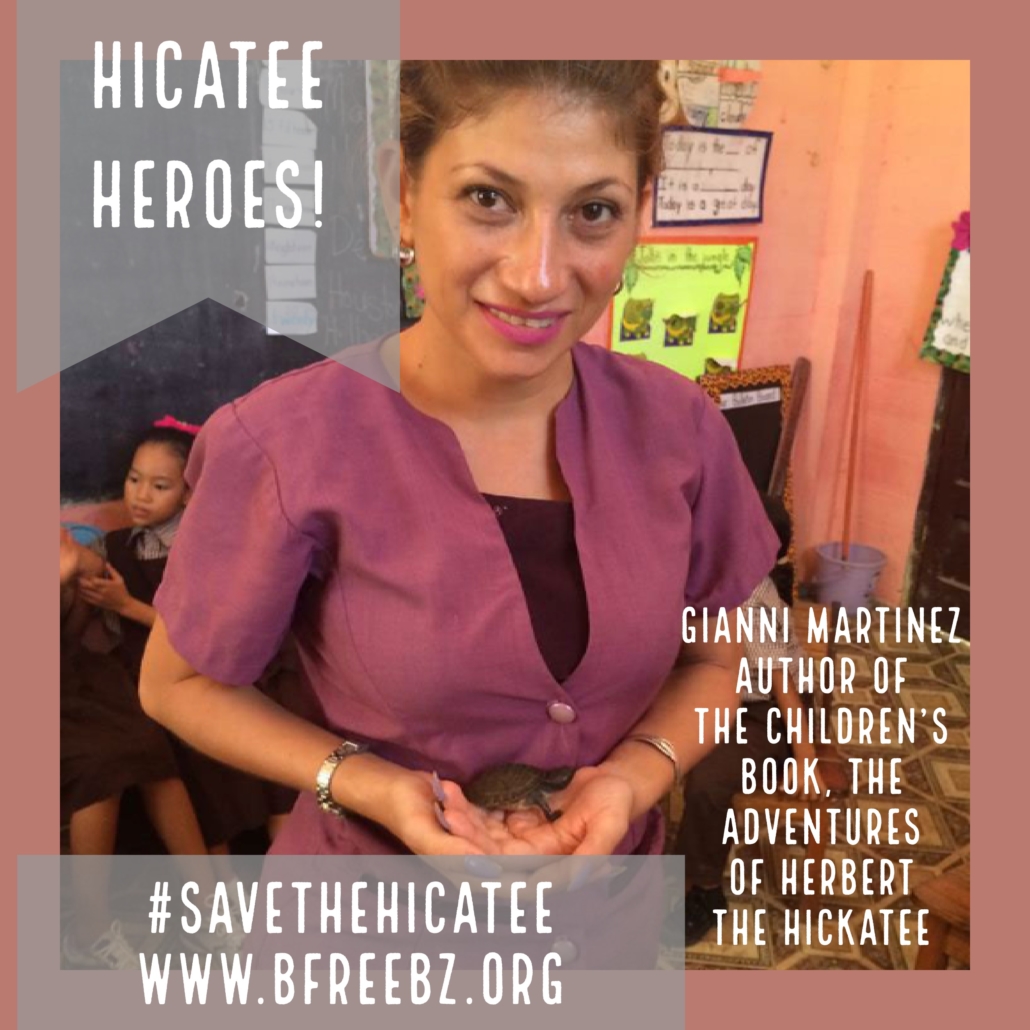

As a result, Hicatee Awareness Month was born in October 2017 as a national campaign to save the species. “Hope for Belize’s Hicatee” documentary was the centerpiece and schools and NGO partners throughout Belize partnered in ensuring that film viewings and events happened throughout the month. We featured a different #HicateeHero every day in October and shared knowledge about how cool it is to be a teacher or researcher or student or biologist and told stories about everyday heroes. We reached hundreds of students and community members in person throughout Belize and thousands online.

When October 31st rolled around in 2017, I was proud and relieved to have made it through. I also thought that would be the end of Hicatee Awareness Month, because I had only envisioned it as a one-time event. However, I started to get emails and requests about what next year’s celebration would look like. And so, it continued….

In 2018, we hosted a national poster contest and had wonderful entries from all over the country. We were thrilled when the Standard IV class at Hummingbird Elementary in Belize City formed their own Hicatee Committee and used materials we sent to teach kids throughout their entire school.

In 2019, we produced a calendar with the winning poster entries from 2018. Those calendars were included as one of the new materials in the 100 packets that were distributed that year.

Then, there was the 2020 pandemic. And the small BFREE team was running short on new ideas for the month, so we decided to form a committee and invite members from other districts in Belize to contribute a fresh perspective to the annual celebration. The results were beyond our expectations! Soon, the team created a new mascot, Mr. Hicatee, as well as activities including a new sing-a-long song and Hicatee Hero video. Packets were delivered by committee members to schools in the districts where they lived. This was incredibly important that year because teachers were required to send materials home with students.

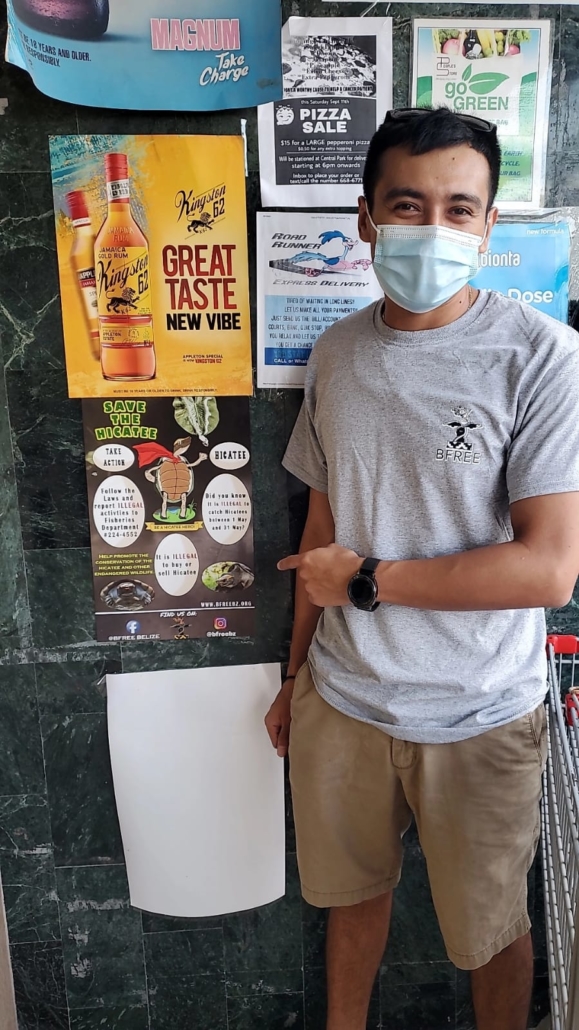

In 2021, new materials included a poster and bumper sticker to target older audiences. These materials were distributed throughout Belize on buses and cars, in grocery stores and other locations.

In 2022, Committee membership expanded and so did our reach. This year, we continued to focus on adult audiences, creating tote bags and even a billboard asking Belizeans to Follow the laws of Belize to protect all wildlife including the Hicatee. We shifted our language to talk about the importance of protecting the watersheds that Hicatee inhabit.

This year, we continue our quest to see the Hicatee become the National Reptile and to ultimately save a species from extinction. I couldn’t be more excited and proud of what we (a growing community of people who care about Belize’s wildlife and wildlands) have accomplished. Our next steps will be to put a research team together who will go into the field to learn about Hicatee in the wild and to collaborate with the communities who share the waters with these special turtles.

The Hicatee is disappearing, but together we can save it.

Since 2017, Hicatee Awareness Month milestones include:

- More than 2,000 pages of printed educational materials, including fact sheets, coloring pages, writing prompts, and more, have been delivered to educators across Belize.

- Those same educational materials are made available for free online in our Online Toolkit and emailed to more than 500 principals and teachers each year.

- We have distributed Hicatee-themed items including: 500 t-shirts, 5,000 stickers, 200 posters, 160 “Herbert the Hicatee” books, 100 tote bags, and 100 “Hope for Belize’s Hicatee” DVD’s.

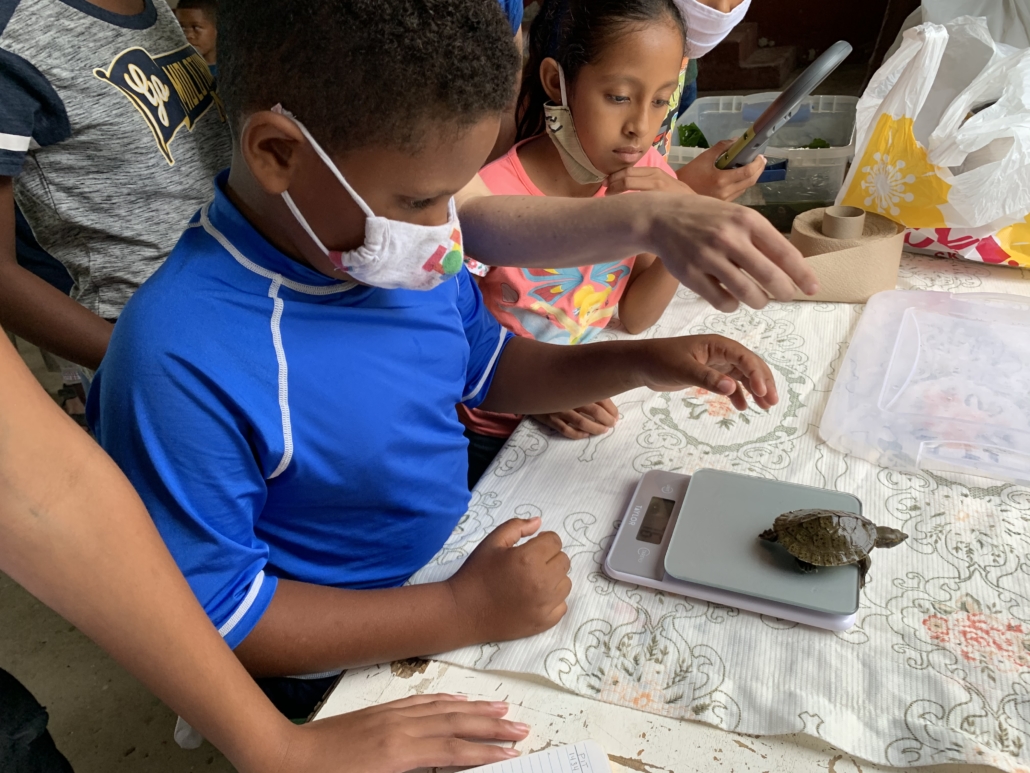

- Hicatee Hero volunteers hosted over 50 public events and classroom visits.

- More than 25 features on radio, TV, and in printed magazines and newspapers.

- Created “Mr. Hicatee,” a catchy sing-along video and song.

- Featured two roadside billboards in strategic locations in Belize.

- Over – local and international visitors to BFREE have taken the Hicatee pledge and signed the Save the Hicatee banner!

Thanks to 2023 Committee Members: Ornella Cadle (2023 Committee Chair), Colleen Joseph, Jessie Young, Claudia Matzdorf, Barney Hall, Abigail Parham-Garbutt, Jonathan Dubon, Ingrid Rodriguez, Jaren Serano, and Heather Barrett.

Thanks to past Committee members: Robynn Philips (2022 Committee Chair), Tyler Sanville, Marcia Itza, Belizario Gian Carballo, Monique Vernon, Celina Gongora, Gianni Martinez, Ed Boles, and Elvera Xi.

We are also grateful to our local and international partners who have supported Hicatee Awareness Month over the years: Turtle Survival Alliance, Independence Junior College, University of Belize, the Belize Zoo, Crocodile Research Coalition, Sacred Heart Junior College, Hummingbird Elementary, Zoo Miami, South Carolina Aquarium, Disney Conservation Fund, and Zoo New England.